description of activity

Media Misinformation (adapted from Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training, Ireton, Cherilyn , Posetti, Julie

This activity relies heavily on examples. Trainers should prepare some examples to explain the different types of misinformation to participants.

Play the video of Kerry Ann Conway embedded in the The Guardian article to your participants. Ask them whether they have heard of this event before. Show them the full article, including the video where Republican Senator Ran Paul repeats the claim.

Introduce participants to the concept of misinformation, disinformation and mal-information (see tip for trainers). Ask them under which of the three categories they think Conway and Paul’s statement fits.

Next, it is time to introduce other forms of communication that can be understood as misinformation or disinformation. Show your participants the list below and ask them to break into small groups and find examples for some of these types of misinformation/disinformation.

- Satire or Parody: no intention to cause harm, but has potential to fool.

- Misleading Content: misleading use of information to frame and issue or individual

- Imposter Content: when genuine sources are impersonated

- Fabricated Content: new content is 100 false, designed to deceive and do harm

- False Connection: when headlines, visuals or captions don't support the content

- False Content: when genuine content is shared with flase contextual information

- Manipulated Content: when genuine information or imagery is manipulated to deceive

Or you can find relevant examples and discuss them with the participants. Below you can find examples specific to Ireland/English speaking countries.

Satire or Parody

Ask your participants whether they know the story and how believable it is. This is an Irish satiric site. Including satire in a typology about disinformation and misinformation, is perhaps surprising. Satire and parody could be considered as a form of art. However, in a world where people increasingly receive information via their social feeds, there has been confusion when it is not understood a site is satirical.

False Connection

As participants how believable is the post. When headlines, visuals or captions do not support the content, this is an example of false connection.

The most common example of this type of content is clickbait headlines. With the increased competition for audience attention, editors increasingly have to write headlines to attract clicks, even if when people read the article they feel that they have been deceived.

Misleading Content

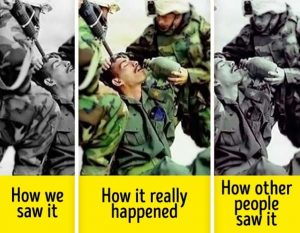

This type of content is when there is a misleading use of information to frame issues or individuals in certain ways by cropping photos, or choosing quotes or statistics selectively.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32579598

False Content

One of the reasons the term ‘fake news’ is so unhelpful, is because genuine content is often seen being re-circulated out of its original context. For example, an image from Vietnam, captured in 2007, re-circulated seven years later, was shared under the guise that it was a photograph from Nepal in the aftermath of the earthquake in 2015

Imposter Content

There are real issues with journalists having their bylines used alongside articles they did not write, or organisations’ logos used in videos or images that they did not create. And here is a list of some of those sites.

Manipulated Content

Manipulated content is when genuine content is manipulated to deceive.

Fabricated Content

This type of content can be text format, such as the completely fabricated ‘news sites’.

https://www.breitbart.com/politics/2019/07/29/aussie-children-taught-to-reject-kisses-hugs-with-grandma/

ASSESSING THE LEARNING OUTCOMES

The aim of the exercise is for participants to be aware of the different levels that misinformation operates and what to look for when looking for information. The learning can be assessed throughout the discussion and the finding and discussing the different forms of communication.

information on the activity

This activity will show participants the mechanisms to spread so called "fake news" to audiences using traditional and online media.

Learners are able to

apply existing journalistic research skills regarding verification of information and sources with regard to reporting on migrants, ethnic/religious minorities, LGBTQIA+, people with disabilities, women, youth and senior citizens

INFRASTRUCTURE

Wifi

A room with chairs and tables

EQUIPMENT

Laptops, tablets or smart mobile phones for the research

Laptop, Projector and PC speakers

MATERIALS

Pens and several copies of the table on the misinformation, disinformation communication (see under Description of the Activity).

DURATION

60 minutes

RECOMMENDED NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS

4-12

TIPS FOR TRAINERS

This activity relies heavely in examples. Part of the activity will require participants to find examples of the different types of misinformation, but some might be prepared by trainer, just in case learners cannot find them.

There have been many uses of the term ‘fake news’ and even ‘fake media’ to describe reporting with which the claimant does not agree. A Google Trends map shows that people began searching for the term extensively in the second half of 2016.In this activity participants will learn why that term is a) inadequate for explaining the scale of information pollution, and b) why the term has become so problematic that we should avoid using it.

Unfortunately, the phrase is inherently vulnerable to being politicised and deployed as a weapon against the news industry, as a way of undermining reporting that people in power do not like. Instead, it is recommended to use the terms misinformation and disinformation. This module will examine the different types that exist and where these types sit on the spectrum of ‘information disorder’.

This covers satire and parody, click-bait headlines, and the misleading use of captions, visuals or statistics, as well as the genuine content that is shared out of context, imposter content (when a journalist’s name or a newsroom logo is used by people with no connections to them), and manipulated and fabricated content. From all this, it emerges that this crisis is much more complex than the term ‘fake news’ suggests.

Much of the discourse on ‘fake news’ conflates two notions: misinformation and disinformation. It can be helpful, however, to propose that misinformation is information that is false, but the person who is disseminating it believes that it is true.

Disinformation is information that is false, and the person who is disseminating it knows it is false. It is a deliberate, intentional lie, and points to people being actively disinformed by malicious actors.

A third category could be termed mal-information; information, that is based on reality, but used to inflict harm on a person, organisation or country. An example is a report that reveals a person’s sexual orientation without public interest justification. It is important to distinguish messages that are true from those that are false, but also those that are true (and those messages with some truth) but which are created, produced or distributed by “agents” who intend to harm rather than serve the public interest. Such mal-information – like true information that violates a person’s privacy without public interest justification - goes against the standards and ethics of journalism.

Notwithstanding the distinctions above, the consequences on the information environment and society may be similar (e.g. corrupting the integrity of democratic process, reducing vaccination rates). In addition, particular cases may exhibit combinations of these three conceptualisations, and there is evidence that individual examples of one are often accompanied by the others (e.g. on different platforms or in sequence) as part of a broader information strategy by particular actors. Nevertheless, it is helpful to keep the distinctions in mind because the causes, techniques and remedies can vary accordingly.

At the same time, it would be absurdly simplistic to suggest that facts are perfect characterisations of the world and that humans are entirely rational beings who incorporate new facts flawlessly regardless of previous belief and personal preferences.

Each of us comes with cognitive and other biases — essentially mental obstacles — that can get in the way of absorbing new factual information. It is crucial to stress that this is not something that happens to other people, it happens to all of us.